In the last Cinemulatto post I discussed Eartha Kitt’s life-long identity crisis and difficult childhood, and her ability to nonetheless enjoy a successful career. I’ve been fortunate to experience my own level of success and contentment: I consistently got straight A’s until my junior year of high school (when I got a B in math), I was the valedictorian of the Duarte High School class of 1987, I was the first in my family (and I believe city) to go to Stanford University, I’ve been the recipient of multiple creative awards, I have a great job, I’m surrounded by wonderful friends and a tight-knit artistic community, and I have an amazing and loving wife and family. I often describe myself as “blessed”. I also often wonder—because of good fortune, not bad circumstances—why me?

Again, in Paul Tough’s book How Children Succeed, there are a couple of key findings—from years of research in neuroendocrinology and stress physiology—that have changed the way I view certain pivotal moments of my childhood:

- If a child receives nurturing and emotional attentiveness from a parent or caregiver, particularly during the first year of life, that child is more likely, as an adult, to avoid depression, drug abuse, chronic unemployment, and unsuccessful relationships. Conversely, children whose caregivers respond to their emotional needs during the first year are much more inclined to deal effectively with stress and adversity.

- Getting a child to think of character not as a set of fixed traits but as something that’s constantly developing and malleable instills confidence and drive in that child.

As I’ve mentioned on this blog before, my mother was schizophrenic. The first time she was admitted into an institution was in 1965; records I uncovered during my childhood indicated she’d been at Metropolitan State Hospital in Norwalk, California. I don’t recall the dates of her time there, but 1965 was the year of my older brother’s birth. He’s not someone I discuss openly very often, and only to close family and friends. After he faked his death in the summer of 2010, I cut off contact with him. He’s an alcoholic in an abusive relationship who’s never been able to hold down a steady job. He spends his waking hours creating enemies on the message board of a very famous English rock band.

I now realize that there’s no way my mother could’ve provided the nurturing and attention my brother so desperately needed during the first year of his life. My father was also pretty checked out during this time, working long hours at a janitorial job and showing the first signs of his abuse toward my mom. On top of that, my brother’s having to contend with a coming out process during his teen years, the indignities of my father (who called my brother “dummy,” among other things), and the absence of any significant role models all apparently took a lasting toll.

My brother David has wrestled a few demons, for sure, but now he’s living his life mission, doing important work around compassion.

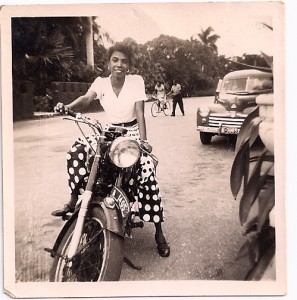

And me? I’m certainly not without my issues. As an adult, I spent ten years in therapy to develop strategies for addressing these issues. Still, I remember the first years of my life as being positive ones, and stories from my aunts throughout my upbringing confirm that my mother was lucid, positive, and loving during the time when I most needed it. She didn’t know what my gender would be before my birth, but after the doctor recommended that she have an abortion due to the health threat, she insisted, “I’m going to have my daughter.”

It was this foundation that created a child, who as a student of Head Start, had the deep confidence that she could run faster than her teacher. When he won the race, I was confused and thought something had gone wrong—not that I had done something wrong or lacked any inherent talent. I went on to be high school league champion in the 300-meter hurdles. In one memorable race, the mile relay, our star athlete was injured, and my coach decided to put a couple of the faster girls in the first two legs to try and gain an early advantage. I ran first. As I approached the 200-meter mark, I thought I’d slow down. Something in me, however, thought, “Speed up.” I gained a wide lead for our team, which was unfortunately lost during the course of the final three legs.

As for constant development, I never lacked positive role models who advised me on character: in addition to my mother, there were teachers, my aunts (“Bad things will happen; it’s how you handle them,” my Aunt Blos told me), relatives, and church members who provided small flashes of hope and insight along the way. I’m no longer affiliated with organized religion, but the effects of the church when I was a child were significant—Sister Mary Esther bringing me a new pair of shoes to replace the one pair I had, or another woman whose name I can’t recall giving me a job cleaning her house when I was in third grade. My fifth grade teacher, Mr. Sheehan, was also a member of our church. At one parent-teacher conference (the only one I recall from so many during my childhood), he mentioned to my parents that he saw no reason why I couldn’t go on to attend a four-year college. I didn’t fully understand what this meant at the time, but from that moment on, I wanted to go to college, simply because he said I could.

The sense of importance and purpose that these people and experiences instilled in me all contributed to good grades, will power, a strong desire to escape from my family situation, and an enthusiasm and love of life that I note and appreciate daily. Maybe “blessed” is an appropriate label after all. I’m still not sure. Regardless, I’m grateful for those moments that my mother was able to respond to my emotional needs. I’m thankful she gave birth to the daughter she knew she’d have.