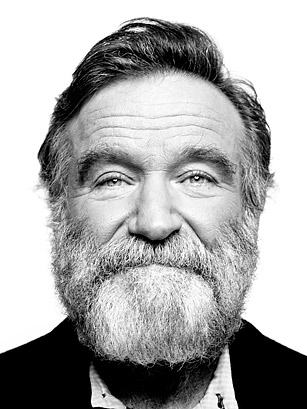

Cinemulatto had to take a break for a couple of weeks. Too much death, too much hate. I’d started writing about Robin Williams right after his passing, so I feel compelled to finish what I started. Here goes….

Cinemulatto had to take a break for a couple of weeks. Too much death, too much hate. I’d started writing about Robin Williams right after his passing, so I feel compelled to finish what I started. Here goes….

“You need to take your wife out of the house more, she’s depressed,” Doctor Gunther told my father. I was around 14 years old. I knew she was sad but at the time didn’t understand the clinical explanation of depression. That is, not until experiencing my own highs and extreme lows around leaving home, coming out, and later dealing with the ebbs and flows of success and failure. Still, I knew this was nothing compared to what my mother had to endure.

It’s with this small insight into the depressive state that I tried to fathom what Robin Williams must’ve gone through. My mother had reason to be depressed. “How can this possibly happen to someone as famous and hilarious as Robin Williams?” we collectively ask, fulfilling denial’s part as the first stage of grief.

In her book Touched with Fire, Kay Redfield Jamison examines past artists who likely suffered from bipolar disorder, and the connection between this disease and creativity. How many more artists, actors, singers, dancers, and other creative people are out there, quietly wrestling demons, contemplating how to cope?

Stars have a mythical quality. We associate them with certain characters they’ve played, or songs they’ve written, or headlines they’ve made, or whom they’ve divorced or married. It’s too often that we find out, after it’s too late, how tortured some of them are. I don’t know how many fan letters Robin Williams received on a regular basis, and I certainly can’t say that such letters would’ve made any difference in his decision to take his life.

We do know, however, that there was an outpouring of love after his death. So, I say to all of you who changed the way I exist in the world, even if it’s just in small ways: thank you. You’re appreciated now and you made an impact.

Viola Davis. Octavia Spencer. Benicio del Toro. Cate Blanchett. The Wachowskis. Mark Ruffalo. Denzel Washington. Dustin Hoffman. Al Pacino. Laurence Fishburne. Catherine Deneuve. Halle Berry. Pam Grier. Prince. Joaquin Phoenix. Morgan Freeman.

The list can go on and on. But, as the passing of someone like Robin Williams gives us pause to reflect on issues of mortality, longevity, creativity, and suffering, let’s also give thanks to those heroes—famous and not so famous—who made us who we are.

Who would you like to thank?